Why we can’t stop thinking about Squid Game

Squid Game is set to be Netflix’s biggest series ever

You’re reading Now Streaming, a weekly newsletter full of what to watch, read, and consume this weekend. It’s part of Netflix Pause, a publication that’s all about hitting pause to reflect on the latest film and TV. Subscribe now to get two free newsletters in your inbox every week diving into screen culture.

Hello, I’m Jared Richards, editor of Netflix Pause — and I keep trying to imagine an Australian version of Squid Game, where childhood games are given life-or-death twists.

The thing is, our childhood games are already pretty deadly: I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one with some scars from a particularly bad game of brandings or bloody knuckles. We also don’t really need any help convincing the world we’re a country filled with things that want to kill you.

Let me know what games could work in the comments, as I know I’m far from the only person thinking about this — this edit of a deadly version of the ‘Beep Test’ brought back a lot I’d repressed.

I’m also far from the only person obsessing over Squid Game more broadly, too. Normally Now Streaming focuses on a new release, but considering the phenomenon Squid Game’s become, it feels silly to not write about it (I wish I could act smug because I knew it’d be huge, but it’s also nice when something’s smash success is a surprise). The nine-episode Korean thriller has hit #1 in 90 countries since premiering on Netflix on September 17, and is on-track to become Netflix’s biggest show ever. And in Australia, it’s been in our top ten titles for ten days, and has sat at #1 for the past seven days — marking the first time a Korean title has landed at #1 in Aus.

Let’s unpack why, beyond the simple fact that it’s really, really good.

Now Streaming

Watch trailer

Squid Game

In case you’re not across it, here’s Squid Game’s premise: 456 down-and-out Koreans in extreme debt are offered what appears to be a lifeline by a stranger: call this number, and you could win up to 45.6 billion won (around $53 million AUD) by playing six children’s games. Oh, and if you lose, you’ll face your immediate and gruesome death.

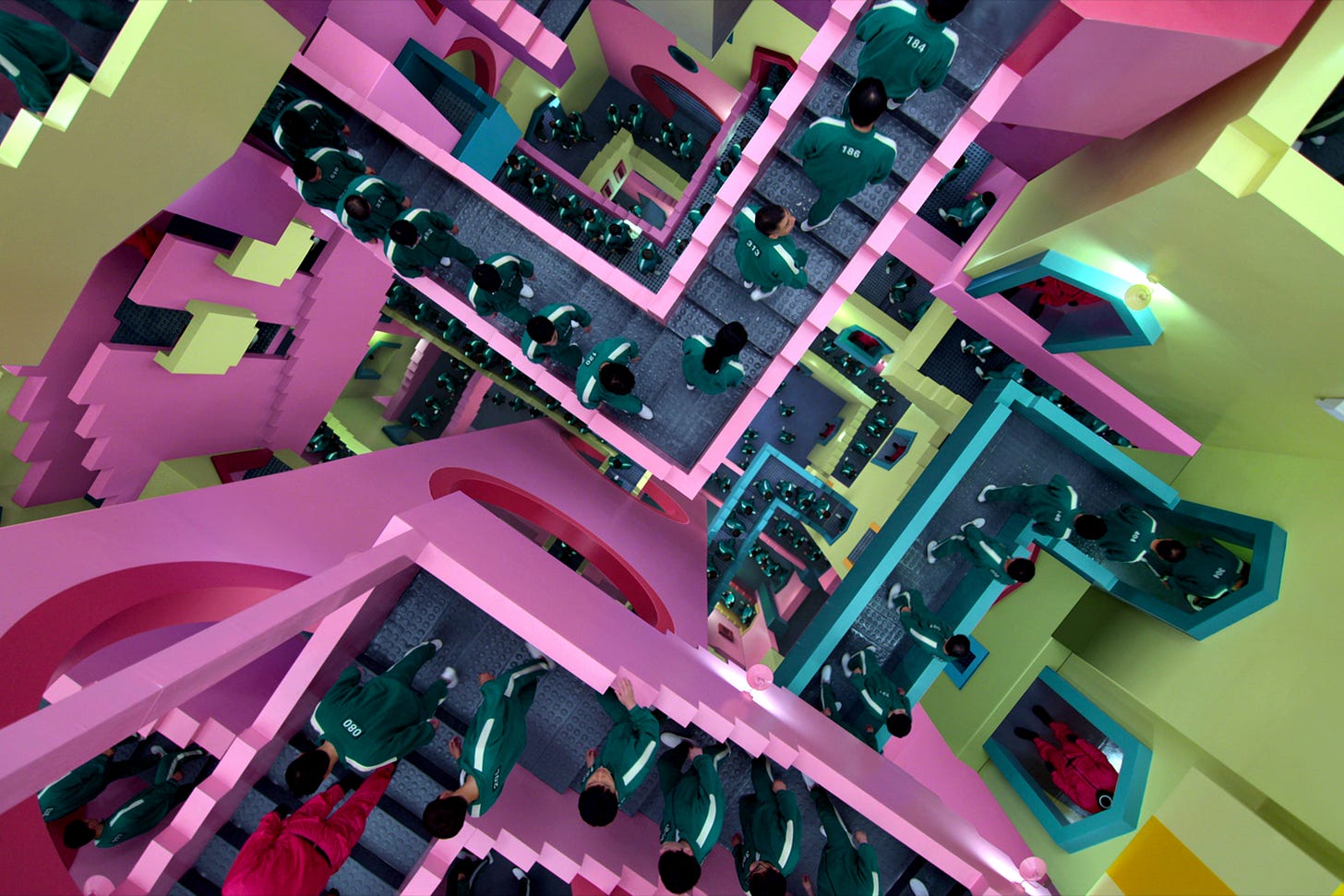

It’s as if Japanese cult classic Battle Royale or its death-match counterpart The Hunger Games were mixed together with Saw — but if Jigsaw dropped the whole ‘nightmare public bathroom’ aesthetic in favour of bright colours and game show-style set-ups like those seen in Takeshi’s Castle or The Floor Is Lava.

The first game is a variation of Red Light, Green Light, overseen by a giant robotic doll who is already terrifying — and then she starts killing off those who don’t freeze in time. Each subsequent game is more intense than the last, with devilish plays on the likes of tug-of-war and the titular Squid Game, a physical Korean twist on bullrush that probably caused its fair share of broken bones in real life.

This is a bloody and brutal show: you may feel slightly perverse for enjoying the thrill of it all. Like the best psychological horrors, Squid Game confronts the timeless question: what would you do to survive? But there’s added purpose to the discomfort, with writer and director Hwang Dong-hyuk telling Variety he wanted to strip the survival genre down to its core in order to focus on emotions.

“I wanted to write a story that was an allegory or fable about modern capitalist society, something that depicts an extreme competition, somewhat like the extreme competition of life. But I wanted it to use the kind of characters we’ve all met in real life,” he said.

“As a survival game it is entertainment and human drama. The games portrayed are extremely simple and easy to understand. That allows viewers to focus on the characters, rather than being distracted by trying to interpret the rules.”

Squid Game recalls Korea’s other big screen hit of recent years, Bong Joon-ho’s scathing film Parasite. Both feature desperate characters who hang up their morals to get ahead, after a lifetime of economic and social humiliation. One of Squid Game’s most interesting rules is that the game can end at any point, if a majority of surviving players vote to quit.

But our players — North Korean defectors, chronic gamblers, or those just burdened by bills — are already being killed in quieter, everyday ways by poverty and neoliberal rule, which promises a trickle down that never arrives. As one contestant says, the torture is worse in the real world.

This show is led by spectacular performances, which adds so much resonance and pain to each character (Special shout out to Jung Ho-yeon, who plays the aforementioned defector in, I was shocked to learn, her very first role.)

Presented in glossy colours and with plenty of addictive twists and turns, these macabre games shine a new light on the truth we all try to ignore: those currently thriving in the world are, whether they like it or not, only doing so off the misfortunes of others, and we’re all opting into the game.

Squid Game is now streaming on Netflix.

Watch these too:

Alice In Borderland, a 2020 Japanese series based on a successful manga about teenagers who suddenly find themselves in an abandoned version of Tokyo, competing in a series of dangerous games to survive. Think Squid Game, but with more magical elements.

The Hunger Games, the four-part series based on Susanne Collins’ best-selling books. Chances are you’ve seen them (they hold up on a re-watch!), but if you haven’t, Jennifer Lawrence stars as Katniss, a teenager in a dystopian society who competes in a state-sanctioned death-match between children.

The Floor Is Lava, because maybe you want the game aspect without the death part? Despite the name, this silly game show is a real cool down after all these blood baths.

Circle, a 2015 sci-fi horror where 50 people find themselves in a sick, inescapable game where every two minutes, they have to vote for one person to die next. Only one can survive.

3%, a four-season Brazilian dystopian thriller, where only 3% of those competing for the chance at a better life will survive. Unlike Squid Games, the games themselves aren’t always deadly — but there’s plenty of bloodshed between competitors.

The internet can’t stop talking about:

Squid Game!! I know I just wrote about it above, but I’d be remiss to ignore what everyone else is saying too. Junkee has a spoiler-filled round-up of memes and reactions, Red Light, Green Light has inspired some ridiculous TikTok recreations, and, for a more serious examination, Sydney Morning Herald asked Macquarie University’s Korean TV and film expert Dr Sung-Ae Lee where Squid Game fits within the country’s cultural output.

The just-announced Super Mario film’s cast, which includes Chris Pratt as Mario, Jack Black as Bowser and The Queen’s Gambit star Anya Taylor-Joy as Peach.

The revelations within Britney V. Spears, a new documentary diving into the pop-star’s conservatorship. The Hollywood Review has a detailed 12-point take-away; Time is calling it “chilling”, and fans can’t stop tweeting their own takes, either. And just days after the doco’s release, Britney’s father has been removed by a judge from overseeing the conservatorship, in a win for her legal team.

Nitram, Justin Kurzel’s controversial new film about the Port Arthur massacres. When announced, the film was denounced as insensitive: now it’s out in cinemas, critics are praising it as necessary and harrowing. The Guardian has an excellent rundown with Kurzel about making the film, and Richard Flanagan wrote an evocative defence for why you should see it, including commentary from a survivor.

Midnight Mass and its unique, affecting take on horror. Come for the spooks, stay for the cerebral musings on faith, purpose and addiction: like The Ringer says in a review that compares the show to The Leftovers, “in [creator Mike] Flanagan’s hands, horror unlocks that pain, doubt, and, ultimately, hope that is inherent to the human experience”.

Before we part, here’s my favourite spoiler-free Squid Game meme:

Let me know yours in the comments below!